In the last few posts, I discussed how to interpret “means plus function” clauses and used the U.S. 6,289,319 Patent as an example. In this post, I will continue my analysis of certain claim elements of the U.S. 6,289,319 Patent. I apologize in advance for the length of this post.

Recall from previous posts, the US 6,289,319 Patent contains a single independent claim which relates to an automatic data processing system including: (1) a central processor, (2) a terminal, and (3) a means for linking the terminal to the central processor.

In order to interpret the claims, I started with the central processor and looked at the first element of the central processor element which is:

Means for receiving information about said transactions from said remote sites

For the sake of this series of posts, I assumed the function of this means-plus-function clause is the wording of the claim, which is:

receiving information about said transactions from said remote sites;

As explained in previous posts, once we determine the “claimed function” of a means-plus-function clause, the next step is to determine what structure, if any, is disclosed in the specification that is linked or associated with the function. This structure in the specification determines the scope of the claim element. So, from an infringement analysis perspective, it is important to determine the scope of the claim element. (Of course, if no structure or a clear association to structure can be found in the specification, then the claim element is indefinite, and therefore, the claim is invalid.)

In the last post, I looked for the corresponding structure in the drawings and could find none. So, in this post, I will review the specification and specifically look for any wording that even remotely corresponds to the claimed function of “receiving information about said transactions from remote sites” that is included in the central processor.

The specification of the US 6,289,319 Patent discusses communications between the central processor and the terminals in several places. Because these provisions can be related to the function of “receiving information about said transactions from said remote sites,” I will have to go through the painful process of analyzing each provision. For convenience of discussion, I have numbered each of these provisions and have listed them below:

(1) The system links a financial institution 1, a plurality of self-service terminals at various remote sites 2 and a credit rating service 3 by telephone lines or other means of telecommunication.

(2) The central processor 4 has a communication interface which allows it to access the various terminals 5 at the remote sites and be accessed by them at any time of the day.

(3) A communication control unit 6 associated with the central processor 4 assures an orderly sending and receiving of information between the terminals and the central processor. The communication control unit 6 provides for a quick transfer of batches of information to and from the terminals 5 under direct access memory mode. Direct access memory modes are achieved by means of high speed data exchange units such as those manufactured by Metacomp, Inc. of San Diego, Calif. and sold under the mark METAPAKS.

(4) The central processor 4 is also provided with a terminal monitor and update unit 7 which is programmed for periodically polling the various terminals 5 in order to verify their status and proper operation and to update the data stored in those terminals as may be required.

(5) The central processor 4 of the financial institution 1 periodically sends to the terminals 5 at the various remote sites 2 loan rate information and other data pertinent to the loans available from that institution which are extracted from the loan rate file 9. That information is stored in the various terminals and can be reviewed by an applicant in need of a loan.

(6) The terminal 5 is programmed to compute the credit worthiness of the applicant and to approve or disapprove the loan. Once the loan has been approved the applicant is requested to accept it or reject it. Accepted loan information is transmitted to the central processor of the financial institution and stored in the active case file 11.

(7) Information about loans which have not been accepted on the spot, are also transmitted to the financial institution and stored for a period of time in the quoted case file 10.

(8) The terminal then addresses the financial institution and requests 32 the prior loan quotation stored in the quoted case file 10 of the central processor 4. This is done by the data processor 13 of the terminal dialing the institution phone number through the modem 15 and sending a request message. The terminal goes into a standby mode with its DMA unit 16 waiting for a transfer of information from the line into the RAM memory 17.

(9) The loan quotation, if not already in storage at the financial institution, is transmitted there for temporary storage.

(10) The institution is also notified 65, and the loan is processed through the active case file 11 by the central processor 4.

The analysis:

First, I will analyze the easy provisions. For instance, provision (6) states:

(6) The terminal 5 is programmed to compute the credit worthiness of the applicant and to approve or disapprove the loan. Once the loan has been approved the applicant is requested to accept it or reject it. Accepted loan information is transmitted to the central processor of the financial institution and stored in the active case file 11.

The phrase “Accepted loan information is transmitted to the central processor” is related to the claim function, but it is on the “sending” side of a transmission, not the “receiving” side. Furthermore, this description is simply functional language. In other words it is a description of what it does, but not the “how.” There is nothing in this provision that describes how or by what structure or “means” the information is transmitted, much less how it is received by the central processor. Hence I can eliminate provision (6) from further inquiry because there is simply no indication of structure in this provision.

Similarly, I can eliminate provisions (5), (7), (9), and (10) from further inquiry because these provisions just describe the function or operation and without any indication of the structure necessary to perform the claimed function.

Turning now to provision (1), which states:

(1) The system links a financial institution 1, a plurality of self-service terminals at various remote sites 2 and a credit rating service 3 by telephone lines or other means of telecommunication.

Provision (1) tells us that the financial institution is linked to the terminals by telephone lines or other means of telecommunications. It should be noted that provision (1) does not say that the central computer is linked to the terminals, only the financial institution is linked.

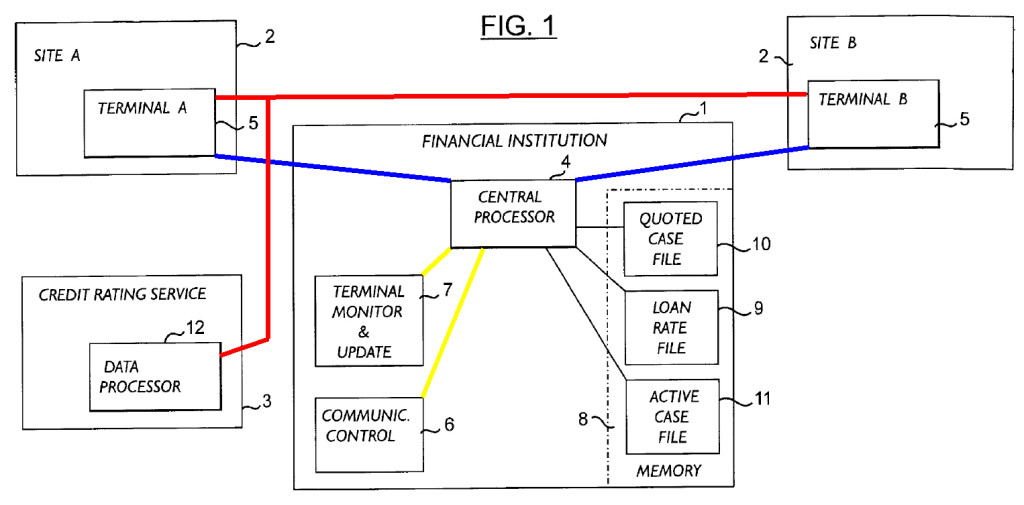

However, assuming arguendo, that the provision is describing the unnamed “blue” lines of Fig. 1 described in the previous post, the structure candidates mentioned is: (1) telephone lines, and (2) other means of communication. Arguably, telephone lines may be sufficient structure, but “other means of communication” cannot be adequate structure. The phrase “other means of telecommunication” is just a functional term. So, this phrase cannot be considered a structure. Thus, our focus will turn to what is left in the provision i.e., “telephone lines.” While telephone lines might be a structure for another function of another claim element, “telephone lines” are not part of the central processor. So, from the language or organization of the claim, we know that we cannot use “telephone lines” as a structure for our function because the function must be also be part of the central processor. We can, therefore, eliminate provision (1) from further consideration.

Going down the list, we now turn to provision (2), which states:

(2) The central processor 4 has a communication interface which allows it to access the various terminals 5 at the remote sites and be accessed by them at any time of the day.

At first blush, the “communication interface” seems like it may be a structure because it appears to be a physical thing. A Google patent search for pre-1986 patents reveals that several “communication interfaces” were known in network technology before the priority date of this patent. So, one skilled in the art of 1986 could apparently have used several communication interfaces as part of a central processor. Provision (2) fails to specify which communication interface the inventor had in mind.

This situation is very similar to a case discussed in a previous post. Recall from previous posts that in Ergo Licensing v. Carefusion 303, 673 F.3d 1361, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2012), the patent claimed a “programmable control means having data fields describing metering properties of individual fluid flows.” Id. at 1363. The patent disclosed a “control device” as the corresponding structure, without any additional details about its design or circuitry. Id. Importantly, the control device in Ergo Licensing could have been one of “at least three different types of control devices commonly available and used at the time to control adjusting means.” Id. at 1364. In Ergo Licensing, the Federal Circuit held that “[t]he recitation of `control device’ provides no more structure than the term `control means’ itself, rather it merely replaces the word `means’ with the generic term `device.’” Id. at 1363-64. Thus, reciting a generic term for an electronic component is insufficient if an ordinary artisan would not associate the claimed component with a specific, well-known structure.

For purposes of this post, one can assume that the “communication interface” of provision (2) is a generic term and not a specific well known structure. In fact, the word “interface” is really a nonce term and can be substitute for means. So, the term communication interface is really equivalent to a “communication means” or “means for communicating” – which by definition is functional – not structural. Thus, we can eliminate provision (2) from further consideration because provision (2) also does not contain any specific structure. Provision (2) only contains a functional nonce term.

Going further down the list, we now turn to provision (3), which states:

(3) A communication control unit 6 associated with the central processor 4 assures an orderly sending and receiving of information between the terminals and the central processor. The communication control unit 6 provides for a quick transfer of batches of information to and from the terminals 5 under direct access memory mode. Direct access memory modes are achieved by means of high speed data exchange units such as those manufactured by Metacomp, Inc. of San Diego, Calif. and sold under the mark METAPAKS.

Again, a Google patent search for pre-1986 patents reveals that “communication control units were common and that there were numerous “communication control units” known in network technology. In fact provision (3) states that the function of the unit “assures orderly sending and receiving of information between the terminals and the central processor.” So, the unit could be some form of router, a network manager, or even just a system bus. Under the logic presented in Ergo Licensing, the mere mention of a “communications control unit” does not provide sufficient structure for performing the function because the communication control unit could have been one of at least several different types of control units commonly available and used at the time to control communications.

Furthermore, the word “unit” is also a nonce term. Consequently, “communication control unit” is equivalent to “communication control means” and hence, does not provide structure.

However, provision (3) goes on to explain:

The communication control unit 6 provides for a quick transfer of batches of information to and from the terminals 5 under direct access memory mode. Direct access memory modes are achieved by means of high speed data exchange units such as those manufactured by Metacomp, Inc. of San Diego, Calif. and sold under the mark METAPAKS.

The reference to this particular piece of hardware may provide sufficient structure for a function. However, it appears that these high speed data exchange units were in the terminals – not the central processor. Note that “high speed data exchange units” is plural and so are terminals. Furthermore, the provision states that “the terminals 5 under direct access memory mode.” The provision goes on to explain that “Direct access memory modes are achieved by means of high speed data exchange units.” However, it appears that DMA mode only occur at the terminals – not at the central processor. This interpretation is also consistent with Fig. 2 which shows a DMA unit as part of the terminal and has direct links to the memory of the terminal. A portion of the terminal of Fig. 2 is reproduced below:

As illustrated above, the DMA or Direct Memory Access Unit 16 communicates directly with the RAM memory 17, which in turn communicates with the data processor 13. Contrast this arrangement to Fig. 1 of the Central Processor illustrated below:

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the communication control unit 6 does not seem to communicate directly with the memory 8 of the central processor. Thus, it is unlikely that the communication control unit 6 somehow operates in a DMA mode.

However, assuming arguendo, that a Metacomp’s high speed data exchange unit was actually included in the communication control unit 6, there is still no clear link or association in the specification linking the Metacomp unit to the function of receiving information from the terminals. Fig. 1 shows the communication links going directly into the central processor 4 – not the communication control unit 6 (see above). Recall from previous posts that simply being able to identify structure in the specification is not enough for a means-plus-function clause. The structure must be clearly linked or associated with the function of the clause. Because there is no clear link at the central processor, we can eliminate provision (3) from further investigation.

Working our way further down the list, we now turn to provision (4), which states:

(4) The central processor 4 is also provided with a terminal monitor and update unit 7 which is programmed for periodically polling the various terminals 5 in order to verify their status and proper operation and to update the data stored in those terminals as may be required.

Again the inquiry is to determine whether one skilled in the art in 1986 would recognize “a terminal monitor and update unit” as a specific piece of hardware or software (which could indicate structure) or whether this is just a generic or functional nonce term which is only indicative of the function of the unit.

A Google search does not indicate that one skilled in the art would associate a “terminal monitor and update unit” with a specific piece of hardware or software. So, this particular phrase appears to be a term invented by the inventor or the inventor’s patent attorney. In reality, however, the term “unit” is similar to the term “device” in that it is a nonce term which can be substituted for “means.” So, the terminal monitor and update unit is equivalent to a “terminal monitor and update means” or a “means for monitoring and updating the terminals.” Thus, once again, there is no structure associated with the “terminal monitor and update unit.”

Furthermore, even if the phrase “terminal monitor and update unit” somehow could contain structure, there is no clear association or link of this unit to the function of “receiving information about said transactions from said remote sites” – especially because Fig. 1 shows that this unit is not even in the communication path and is bypassed altogether. We can, therefore, eliminate provision (4) from further consideration.

As discussed above, provisions (5), (6), and (7) have already been eliminated. Now turning to our last provision which could possibly relate to our function, we will investigate provision (8), which states:

(8) The terminal then addresses the financial institution and requests 32 the prior loan quotation stored in the quoted case file 10 of the central processor 4. This is done by the data processor 13 of the terminal dialing the institution phone number through the modem 15 and sending a request message. The terminal goes into a standby mode with its DMA unit 16 waiting for a transfer of information from the line into the RAM memory 17.

Unfortunately, for Landmark Technologies (the exclusive licensee of the US 6,289,319 patent), provision (8) only appears to discuss what the terminal is doing. The provision states “the terminal then addresses the financial institution” and this is done by “sending a request message.” But there is no mention of the structure involved with “receiving any request” on the side of the central processor. The provision states that the terminal dials a phone number through a modem – which at least indicates some structural items, but there is simply no discussion of any structure on the side of the central processor. We simply do not know how the central processor receives the request (i.e., by a modem, router, etc.). But again, even if we can assume that there must be a corresponding modem at the central processor, this “assumed modem” is not clearly linked to the function. So, once again provision (8) fails to provide the appropriate structure corresponding to the function of this means-plus-function element.

In summary, the specification does not appear to contain any disclosure of structure (or a clear linking a structure) within the central processor that could perform the function of “receiving information about said transactions from said remote sites.” Without being able to clearly identify the structure, the public has no way of interpreting the scope of the claim. When this occurs, courts hold that the claim element is indefinite and therefore, the claim would be invalid.

Today, the function of “receiving information about said transactions from said remote sites” is a pretty standard function – one of which can be performed by almost any computers. Would a court really invalidate this entire claim if the patent attorney simply failed to put in a structure for this function? Because this post is already horrifically long, I will answer that question in my next post.

For more information on this complex subject of means-plus-function claim interpretation, feel free to contact Bill Naifeh at www.naifeh.com.